P.S. David would like it to be know that he, David Vanderford Celis, came up with the idea for the blog. No one wants to incur his wrath.

Blog space for critical reflections on course material for Culture Wars: Politics, Ethics, + Aesthetics

Well it looks like this class is over. But why let this blog go to waste? I’ve always wanted somewhere to write about my daily activities so I think I will take the opportunity to share them with the other members of my class.

Today I had a physics review, so I had to get up kind of early. 9:30, which was early compared to when David woke up. He said the only thing he remembered from this morning was me opening and shutting the door about twenty times. That’s why when I sleep, I use earplugs.

Some drunk people were hollering over their game of Madden NFL this morning, which made me want to go home even more. I kind of miss my dog too.

Shea went home today and David and I were a bit upset to see her go. We’ll be pretty bored as we play Dawn of War and World of Warcraft until Friday.

I think tension is starting to mount between me and David. Today he made a post on his blog about how loud my rave music is. I wear headphones so he doesn’t have to hear it! Ughhh maybe I should tell him how annoying it is to hear him studying late at night when I try to go to bed at 11 pm. Those page turns don’t need to be that loud. I don’t know how I’m going to live through another semester like this!

1.) War images become “official” through repetition and their power to symbolize ideologies. The image achieves this “official” status from government and media support. It is backed by the government’s effort to keep it in circulation, and the media prints it in magazines and newspapers, plasters it on billboards, and floods the televisions. War becomes a single moment, whether in a real photograph or a cartoon-drawn image, and ideas are represented within this moment. The reason these ideas are supported by the government and by the people (either of their own accord or as a result of the government-supported media portrayal) is that they confirm specific identities of the nation that are desirable in a time of war. These identities are based on patriotism and concepts the nation considers itself to hold valuable, such as human rights and environmental welfare. The “official” image depicts exactly what mass society wants to believe about its government and the role it plays in the war. It embodies the very reasons we justify our fighting, as well as the reasons we believe our cause is worth soldiers’ lives. We want to believe that our part in the war is for the better of the world, and so the “official” image strokes our ego and confirms this for us. Inevitably the image possesses a political agenda, but it is one we want to uphold as a nation. “Official” war images serve exactly the purpose Plato describes in The Republic, one of empowering the nation toward unification and progress.

The following images satisfy their position of being “official” through similar portrayals of American ideology. The first displays an American soldier helping a small Iraqi child. Not only does this show the generosity and compassion of Americans in bringing medicine to those less fortunate, but the happy mother in the background shows us approval and gratitude for our actions from the Iraqis. The second image shows Muslims and Christians working together to reopen St. Jude’s. This image becomes a sign that

2.) In “Regarding the Torture of Others” Susan Sontag may present the argument that images should be ignored as ideological and that we should focus rather on the events depicted by the photo. But this she addresses as a factor in the corruption of American leadership. Sontag herself does not deny the capacity of photographs to hold ideological values. She recognizes that they are causing an issue not just because of “what the photographs reveal to have happened,” but also as a result of more implicit meanings the images possess. Sontag addresses that a further problem is that the pictures were used as “trophies” and the “perpetrators apparently had no sense that there was anything wrong in what the pictures show.” She hardly wants us to ignore the images as separate from ideologies when she makes the claim that they illustrate the “culture of shamelessness (and) the reigning admiration for unapologetic brutality” that has increasingly become accepted as entertainment in

An analysis of the pictures and not necessarily of their depictions, however, reveals even further portrayals of ideologies. As Susan Libby explains in her “Culture/War” article, elements of the picture itself such as camera angle, character of being an “everyday picture,” gaze of the people present, and even the fact that someone controlled the camera as the picture was taken all play a part in a picture’s ideological implications. These specific aspects when applied to the Abu Ghraib photographs reveal principles of domination, control, and inequality (Libby). They become dangerous as they are circulated to the public, and these ideologies are presented to society through the visual representations.

What is depicted in the Abu Ghraib photos directly reflects many of the same ideologies that can be found in the analysis of the pictures as vernacular photography. This can actually lessen the degree of harmful potential because those who do not accept the explicit are likely to not accept the implicit either. Thus in this case viewers of the public can reject the violence they see being depicted simultaneously with the latent ideas of domination and control. As Libby points out, visual representation is about “controlling our knowledge,” something that is utilized heavily in the political world. The real dangers arise when ideologies are imbedded within a picture that people accept. The best example of this concept is a picture that actually depicts something agreeable with the viewer, but is imbedded as an image with ideological ideas possessing harmful values. An image previously discussed in this course, Roses for Stalin by Vladimirski shows an agreeable photo of children giving roses to Joseph Stalin. Some underlying messages here that can be delivered furtively through the positive exterior are of communism, dictatorship, and male domination. This idea of the public more readily identifying accepting the explicit part of the image and consequently accepting the implicit is discussed in “Mass Media and the Public Sphere” as the “hypodermic effect” effect of mass media. This refers to “an increased passivity in viewers ‘drugged’ by media texts with less explicitly political messages.” When performed, it can become a “means of domination” on the masses of people by “‘selling’ them ideas through the media” (Sturken). Photos can have the same effect even if they have parallel meanings, but that are used to represent something that is not congruent with the two. Take the example of when only pictures that project a positive image of our efforts in a war are shown. The actual depiction may be something positive just as the ideologies represent (see photos from question #1), but they do not offer the full scope of the situation. The negative aspects are not represented. As to what is harmful ideology is to a degree up to discretion, but when the minds of the masses can be controlled by hidden or completely absent ideologies, there is great danger in the corruption of societies.

The separation of the photos from ideologies does make for successful politics, though. Those in the Bush Administration can then claim to be shocked and appalled at the photos, since they do not represent the “‘true nature and heart of America’” (Sontag). This separation, though, is like putting on a neck brace—they can cover up the problem and prevent further damage, but they are not actually going in and reconstructing and fixing the framework. And yet do we blame them so readily without any ideas of alternative methods? Analyzing ideologies and working to change them requires the removal of longstanding accepted ideas. Not only does it require the deconstruction of present ideologies, but new ones must be ready to successfully establish in their absence. This takes a great amount of time and effort, and the people of a country need immediate attention as well as perseverance through time. And we cannot forget that new ideologies can most certainly not be accepted or instilled by authorities who the masses do not trust.

2.) With all of this in mind it is important not only for those in control of the dissemination of images to be conscious of the vulnerable public they are providing for, but it is important for us as viewers to be critical of the information we are presented. Censorship has many fine lines, and there should be differences between what can be shown in an elementary school classroom and what an adult citizen can view by choice. Images of war may be kept from the view of younger audiences, but should not be kept from the public at large, especially the public of the country actually in the war. The exhibition of photographs is just as important during war as during a time of peace. Just because something is already in progress does not constitute the need for its continuation, and photos that question the movement of the war thus become very important in its path. The Abu Ghraib photos provide a perfect demonstration of the horrors of war that we are often sheltered from. Without exhibition, actions may not be accounted for, and the terrible things people are capable of can be allowed to proceed. By excusing accountability we often excuse responsibility, and not only can actions continue, but the dangers can escalate if those performing them have no one watching and thereby no one holding them accountable. Alas it is evident that even the exposition of these horrors does not always lead to their demise, but we cannot expect anything to change if the images remain hidden from the public eye.

1. War images can become official through government or media proclamation. In either case, such images must be easily recognizable and also emotionally charged in order to come into widespread use. These images are usually propagated by the media, which will reuse them again and again in order to avoid the need to find new material of the same quality, and because of viewer identification with the images due to familiarity. If the images reinforce a particular view of a war, then this view must be held by a large majority of the people in order to become well known.

The first image, perhaps the most widely known so far of the Iraq War, is of the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue after the invasion. There are actually hundreds of images of this – because it was staged as a media event by the military. Civilians were brought in from a village to produce a fake crowd, and they watched as the statue was pulled down. In most photographs, it appears as if a large crowd was present but this was due to the framing of the picture. In this particular shot, the large empty areas can be seen, making it evident that support for

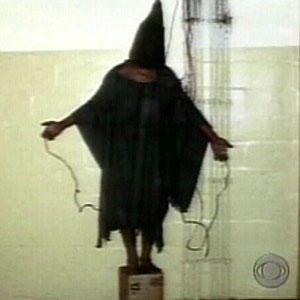

The photograph of a detainee in a black shroud and hood standing on the box is the most often reproduced image of the Abu Ghraib photographs, which number over eighteen hundred. This image is most often used because it is not offensive, and the media tries to self censor itself in order to keep viewers. The more sexual Abu Ghraib photographs are typically not shown. Also the anonymous man (who has since been identified, but he is still masked) stands on a box that resembles a pedestal, while spreading his arms in the typical pose of the martyr – the cross. But instead of having his hands nailed, they are attached to electrodes, a more modern version of a painful death. These images were originally taken to serve the interest of the soldiers who conducted interrogations, but now they have been used by anti-war activists as the icon of protest.

A picture from a gallery on the official White House website entitled “Photos of Freedom” shows marines distributing food to civilians. The behavior in the photograph is civil – there are no riots breaking out over limited rations. The truck is also fully loaded with supplies – showing

2. While I believe that the need for reform emphasized by images such as the Abu Ghraib photographs are a primary concern, I think that downplaying the images as Sontag suggests will lead to a lesser understanding of the events themselves. We must understand what we decide to condemn, and only by deep examination of the images can this be done. The most important thing to ask about any image is “why was this created?” The answer to this will reveal the bias. All photographs are biased, since they only offer an edited version of reality. Only what lies between the borders of the lens, and happened in the fraction of a second of exposure is often promoted as a true and unbiased account, although it will be laced with ideology.

The irony here is that the Abu Ghraib photographs were taken by soldiers promoting the abuse, but now they are used to condemn it. The conflict in ideology seems almost sick – the soldiers smiling behind the naked bodies of detainees forced into humiliating poses. While with one photograph there is some doubt about the events that occurred around it, and the image’s staging, there is much less doubt with a series. There were over eighteen hundred photographs of the Abu Ghraib incidents, which showed the evolution of different torture sessions so that some sense of the passage of time could be gained through still images.

While these considerations seem to remove most of the uncertainty around the events, they also continue to propagate the misconception that photographs are a perfect form of truth. Just because some photographs tell the same story that occurred does not mean that others will be so candid. These misconceptions are harmful to visual literacy and the examination of ideology behind images – the lack of such scrutiny leaves one vulnerable to propaganda.

3. In a democratic society, the voters must be informed politically in order to make the most informed decisions. Withholding any sort of information necessarily compromises this, yet there are instances of national security where the public must be kept in the dark. But the effect of a war is not one of these areas. The public needs to know what exactly they are voting for directly, or what their elected representatives are voting for. If the war has gone into stalemate, the “enemy” is being tortured for dubious reasons, and civilians are dying, then people must know so the war can be reconsidered with these factors in mind.

There is a difference between images of offensive and defensive conflicts. The offensive conflict is inherently an ethical issue, since a decision must be made to engage in violence or not. A defensive conflict presents no option – rise and fight, or be annihilated. If there is no justifiable reason to be engaged in offensive conflict, then the citizens of a nation have a right to make the decision to end it. Also, war should not be used as a common tool to force the compliance of smaller, less stable nations. War devastates everything, and supporters need to know the consequences of authorizing violent force. There should be no censorship whatsoever in this case.

In a defensive war, the nation’s very existence may be at stake. But if there is no threat of annihilation, then involvement should be minimal and not include “revenge” actions, such as the Iraq War today. Thus again, there should be no censorship of war images, so that the public does not seek out revenge, because of the pain it will inflict on the innocent. This only leads to the escalation of conflict anyway – as we further fight terrorists, we cause more of them to rise up against us than there were to begin with.

When the nation is indeed about to be toppled, as the Soviet Union nearly was in 1941 by Nazi Germany, then the government must do all it can to resist destruction. The injustices inflicted by the government on its own people will be nothing compared to the enemy’s wrath. Certainly censorship of war images to keep morale high would be acceptable as an alternative to rape and slaughter of the citizens, at the hands of some other force. But another alternative would be to use images of violence directed against the “good guys” in order to motivate the nation to stand strong and resist, because the images will remind them of their fate if the nation’s struggle fails.

The Abu Ghraib photographs should not have been withheld from the public. When they were eventually leaked, the negative reaction against the Army was much greater than it would have been if the offending soldiers and been summarily punished. The cover up was a form of tacit approval of the tactics carried out at Abu Ghraib. While I think that the public has a right to know about offensive wars it is engaged in, I do not think the photographs should have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography. Association with an artistic institution almost praises the photographs in a way, because they acknowledge something about the nature of war. But these photographs never should have existed in the first place, so they should not be associated with art. Also, these photographs were taken as trophies by the soldiers, in order to glorify their dominance over the prisoners and also to humiliate them. The victims’ rights should be taken into account, as they were forced to participate in the photographs, and then had them used in blackmail during interrogations. The fear of being seen in such impious poses (the homosexual poses in the context of Islam) by others made prisoners comply, but now thousands of people will see them, adding to the humiliation. The public has a right to know the war though images in the media, and the media will self-censor itself to a large degree, which would filter out the most degrading of the photographs. But putting them up on display is furthering the emotional damage done to the detainees.

Image Sources (From left to right):

http://www.dannyrudd.com/brokenmedia/images/statue.jpg

http://peacework.blogspot.com/uploaded_images/Abu%20Ghraib%20Torture-715244.jpg

http://www.whitehouse.gov/infocus/iraq/photoessay/essay1/09.html

1.) It seems that, in today’s society, images of war, as well as those depicting/representing any significant cultural/political issue, are deemed “official” within American minds when they are given mass media display and commentary. Though one could certainly argue that any explicit photographic images of America’s most recent war with Iraq, such as those taken by American soldiers during their occupation of the Abu Ghraib war prison, are in some way “official” images of the war (being that they specifically depict the actual goings-on of the multinational conflict), these images were only given their “official” status after being widely exposed and explicated on national television and in national news writings. Much of the reason for media exposure being the main qualifier for war images being considered official is the simple fact that only through such exposure are the images able to be viewed by a significant enough amount of people so as to be associated with the particular war that they depict. Another possible explanation for why this method of exposure is a means by which images can gain “official” status is that, by being presented with “professional” commentary concerning the images and their connection to various wars, the viewer subconsciously assumes that such images must be official images of a war if they are given so much attention so as to be made note of by those men and women assumed to hold high places of political knowledge and power.

http://clubtroppo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/whoops.jpg

The above image could certainly have been considered by the American public (following its being displayed on television screens across

the mission having been “accomplished” came just a tad too soon, considering the fact that this image was taken in May of 2003, and that even now, on the very cusp of 2008, the American Military’s occupation and “liberation” of Iraq continues. An interesting side note is the fact that this very image is used for a decidedly opposite purpose by various comedians (i.e. The Daily Show’s John Stewart) today, that being satire regarding the Bush administration and its many follies and false foresights, most notably those concerning its dealings with Middle Eastern nations such as Iraq.

http://theredhunter.com/images/Saddam%20Statue%201-thumb.jpg

Above is an image of an Iraqi statue of Saddam Hussein being uprooted by American soldiers amidst an elated crowd of Iraqi citizens. This image and many others of the same scene were, shortly after their being created, proudly displayed in various forms of American news media. The purpose of the photographs of this scene being shown as “official” images of America’s war with Iraq could very well have been to send the message to Americans that, by invading Iraq, the American government was seeing to the overthrow of a tyrant, hated even by his own people (Iraqi citizens could be seen in video footage of the spectacle happily dragging the remains of the statue through Iraqi streets) and thus pursuing justice within another, less liberated nation.

2.) In regards to the difference of opinion between articles such as Libby’s “Culture/War” and Sontag’s “Regarding the Torture of Others” on whether or not images hold harmful ideological power over the viewer, I must admittedly place myself in a moderate position, with an err towards the views expressed in Libby’s article. I believe it is undoubtedly true that images, in the way by which they are intentionally constructed (by the photographer for instance), in the gaze that they assume, and in the limited amount of space/time that they represent, do depict reality with certain biases, and thus perhaps are not accurate references when searching for the absolute truth regarding any situation, such as that having occurred at the Abu Ghraib war prison. As stated by Libby, “…images are not transparent screens through which the viewer can see some truth beyond.” Thus, no matter how shocking or horrifically inhumane the actions depicted within a photograph may appear, one must consider the setting in which the image was created, the intentions of the photographer, as well as many other technical aspects that go into the immortalization of a moment via photography. Though, because of a certain amount of involuntary human emotional reaction, one is undoubtedly inclined to immediately assume sympathy for people being abused or victimized in images and to likewise assume a disgust for the abusers seen in the same images, it is nonetheless detrimental to the objective viewing/assessment of an image to lose sight of the simple fact that it is an image, and should not, again, be assumed as an absolutely unbiased depiction of an actual happening.

On the other hand, when photographs of inhumane torture such as those taken by American soldiers during their occupation of Abu Ghraib are publicly exposed, a certain number of assumptions concerning the images can and should be made. Being that these images depicting decidedly unnecessary and heartless abuse of war prisoners were taken with a seeming sense of pride by the very abusers seen within them, one can assume that such instances of torture were not staged, and were in fact deemed by a number of soldiers and military officials as acceptable and even humorously entertaining treatment of war prisoners. Thus, when the obvious fact is officially established that the images of the American Military’s treatment of Iraqi prisoners are relatively accurate depictions of what happened in reality, what is subsequently most important is how those seen within the images as committing such atrocities are dealt with, as opposed to close, meticulous philosophizing on the ideological nature of the images, and what that nature might imply. The fact of the matter is that these images were created by American Soldiers as a glorification of their incredibly hostile treatment of other unarmed, and thus defenseless human beings. The moment that images of this nature are presented to the American public, and perhaps most importantly, to American government/military officials, the most important issue on which to focus becomes a swift end to such abuse, and just punishment of those having taken part in it. To focus more intensively on the photographs as images rather than what actions they are evidence of can, in fact, be used as a way of avoiding actually addressing the obvious problem within

3.) It is my strong opinion that war images such as the Abu Ghraib photographs, as well as countless others having been taken of many wars since the dawn of photography, should be made open to public viewing both during and after times of war. Though many might believe it unpatriotic to show any negative images/photographs of American soldiers and their discourse during a time of war with another nation, the result of not making such images open for public viewing is, in my humble opinion, far more detrimental to

Sources:

1.) Sontag, Susan, “Regarding the Torture of Others”, The New York Times, May 23, 2004

2.) Libby, Susan, “Culture/War”, The International Journal of the Arts in Society, Vol. 1, No. 5, 2007

3.) Gogan, Jessica; Sokolowski, Thomas, “Inconvenient Evidence: Iraqi Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib”, at The Andy Warhol Museum, text by Hersh, Seymour M., September 11-November 28, 2004

Ruth E. Day

1.

Images become “official” because they do something to further a certain cause. In the context of war imagery, official images tend to work to further the idea that the war is just and having positive affects. They tend to be patriotic and glorify the soldiers fighting on our side of the war as heroes. They also bay depict the soldiers fighting for the opposition as evil and sometimes terrorists. I have found two images that have achieved official status regarding the war on terror. The first is an image of a statue of Saddam Hussein being taken down by American soldiers in

2.

I believe that images can be harmful, beneficial, or neither depending on who is looking and them and what is in them. For example, the image of the Saddam Hussein statue being toppled can be considered as both beneficial and harmful. It can be beneficial in that it elicits pride in being American and relief over the end of a horrible Iraqi regime. However, it can also be considered harmful in giving Americans a skewed idea of the Iraqi response to American soldiers’ occupation of

3.

I do not believe that images should be kept from public view during wartime. Images can both garner support for a war and reveal the harsh realities of it to the public. That is what the Abu Ghraib photographs did. They showed Arab prisoners being abused and even tortured by American soldiers. They opened peoples’ eyes that it isn’t only the terrorists who are capable of evil acts. American soldiers are as well. They show war as something that is not always glorious and noble but as something where people get hurt and abused and exploited. It leads normally good people to commit evil acts. I am a strong believer that situations such as war and tragedy bring out the best in some and the worst in others. It is important to have representations of both sides. Yes, war does cause some to do many heroic things, such as in the case of Sgt. Smith. However, it can lead others to do evil and to lose their sense of morality and their sympathy for other human beings. This is what happened to the American soldiers at Abu Ghraib. War caused their view of right and wrong to be blurred and to rationalize evil acts. This is why I believe that the Abu Ghraib photographs should have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography. If such images are not made public, those of us whose sense of right and wrong have not been skewed by the experience of war can see both sides of the picture: the side that produces people who we can admire by showing the best of the themselves in times of hardship and the side that produces people who, once they have seen the atrocities that human kind is capable of turn to committing those atrocities themselves.

Image sources:

Statue: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/446366a

Medal of Honor: http://www4.army.mil/ocpa/read.php?story_id_key=7091

Kim Hambright

1. In times of war, countless images are captured via digital cameras, camcorders, cell phones, and other sorts of electronic devices. The images are sent back to the

In the first “official” image, a number of American soldiers form a line in anticipation of some sort of attack. The faces of the men are clearly visible, easily recognized as someone’s son or brother. The interest and intent of this picture, whether conceived purposefully or not, is to gain support for the war. Since the figures are personal, the viewer feels connected to the soldiers, sharing their anticipation, their worries, and their pain. One feels as thought the soldiers are innocent; with their gentle faces and almost timid appearances, these men in uniform can do no wrong. Even amidst what the public knows to be a cruel and harmful place, the viewer sympathizes with the soldiers of the

The second image depicts an Iraqi child and an American soldier. Clearly an anti-war image, the photograph contrasts the stark and barren ground with the chaos of war. The soldier standing on the left with the gun is not immersed in battle, nor can the viewer detect any immediate harm in his proximity. In spite of the current lack of necessity for the soldier to don any extreme means of protection, the photographer captures this American soldier with a gun. Several feet away from the soldier stands a young Iraqi child. He appears to be both enamored and afraid of the grandiose adult standing before him. The viewer cannot help but wonder what is taking place in this image, is the soldier threatening a young and innocent child? Or is the image just a cropped version of a larger scene? Whatever the case, the image appears to capture inappropriate behavior on the part of an American soldier. Anti-war activists would look and the image and be horrified; after all, what is an armed American soldier doing anywhere near children?

2. When answering the question, “Can images be harmful?” one must take into consideration the context of the word harmful. Who or what is one worried about harming? Surely the images of the American soldiers at Abu Ghraib were harmful to the reputations of the soldiers and their families, and likewise the images of the planes hitting the twin towers on September 11 are harmful to

I agree with some of the statements made by Libby, Gogan and Sokolowski that images can be harmful. Surely images of war and violence can be demoralizing and shocking to the public viewer, though I tend to agree more with Sontag. I feel that people are often too caught up with their immediate reactions and emotions when viewing a photograph that they often forget it actually happened. Ignoring the image mutation possibilities created by programs such as Photoshop, I feel that the raw truths of images are often forgotten or misunderstood when viewers focus on their own reactions to the photos. Whether one is afraid, excited, horrified or unsure of an image is irrelevant. In my opinion, artists of war photography rarely take photographs for the sole purpose of indulging the viewer’s emotions. Instead, photographers attempt to capture real life actions, telling genuine stories of the soldiers overseas and their lives. Though the images may be “harmful” or “offensive” to the masses, I feel that it is the duty of war photographers to capture and expose war as it factually happens. Photographs are meant to bring the truth of an event, regardless of how one feels about it.

3. Looking at war images as a whole, and understanding the power they hold, I still feel that the most important thing is education. Censorship in times of war may be necessary, especially when concealing graphic images of deceased American soldiers; however, I do not feel that it should be used to an extreme. The most important aspect of war photography is informing the public. Thousands of miles away from the action, it is nearly impossible for anyone in the

I feel that censorship is warranted when concealing situations that would undoubtedly evoke an uprising in the public. In these cases, censorship, controlled by the government, should not only be acceptable, but encouraged. Along with the responsibility to inform the public, comes the responsibility to protect the governmental structure. It is not this way in all cases though. For example, images of destroyed cities, distraught soldiers and unfair treatment of prisoners have no reason to be censored. Granted, I do not believe that images similar to the ones from the Abu Ghraib prison should be displayed in a museum gallery, I feel that is of the utmost importance that all people of America be informed as to the way the soldiers, supposedly fighting for their country, are acting.

They all put a positive spin on war, depicting it as a courageous and patriotic act.

One image that fits into the category of “winning” is the toppling of Saddam’s statue in

One image that fits into the category of “winning” is the toppling of Saddam’s statue in

Another example of an “official” image relating to the

Another example of an “official” image relating to the

This last image of another TIME cover shows “The American Soldier” as being the person of the year. Three soldiers are seen standing together in uniform, upright, unyielding, and proud of the work they do. This particular image fits into the category terming war as being “manly”; it also, especially with the help of the wording also present, makes the soldiers who represent the war a source of national pride because of the positive way in which they are represented. Such an image that brings soldiers into the pictures really helps to further the interest of the country because the military is one aspect of war that most everybody agrees about: nobody would want to say that they don’t support the military when the people in the military are losing their lives for the protection of others.

Overall, the images work towards gaining a national unity in favor of the war that is occurring. It is also important to note, however, that these pro-state images are not the only ones that make it to the front covers, even if they are the majority and the most likely to do so. Other images, sometimes precisely for the reason that they were first censored and thus caused an uproar, also make the covers (such as the image of a detainee with his head covered by a sack, or about to be “electrocuted” and even to an extent the flag-draped coffins). These, I suppose, are never really “official”, however, as they work to the detriment of those leading the charge.

Aday, Sean, John Cluverius and Steven Livingston. “As Goes the Statue, So Goes the War: The Emergence of the Victory Frame in Television Coverage of the

2) I agree that images have a lot of power which, like all power, can be used for good or bad (depending on how you look at it). This notion goes all the way back to Plato’s use of images to further the state, as well as Hitler’s, and the differing ideas regarding modern art during times of fear and war.

But in the photography of real-life events – photography which was not even done with the idea of propaganda, such as was be the case with the other examples seen as either helping or harming “the state” – should we ignore the images (to an extent) and focus on the events?

First, let me quote Sontag herself and clarify her position: “So, then, is the real issue not the photographs themselves but what the photographs reveal to have happened to ‘suspects’ in American custody? No: the horror of what is shown in the photographs cannot be separated from the horror that the photographs were taken – with the perpetrators posing, gloating, over their helpless captives.” Sontag does not appear to be arguing at all that we should ignore the images at all; rather, she ties the fact that the images were taken to the actions, and then focuses on the fact that these actions occurs. And I totally agree with her.

Torture was occurring even before these pictures “came out”… and there were people who knew about it (as proven in greater detail in part 3). This maltreatment, even if it wasn’t of the same type as the posing which was done for the images that we see today, still existed and was still deplorable. The actions themselves solicit the responses of disgust. The images main role was really in making the actions available to the view of the public… without which, people would not know what was going on in the prisons.

As Sontag said, fact that these people would actually smile at the camera behind the naked detainees and regard the whole event with humor worth saving in the form of a picture is indeed quite horrific; however, the acts themselves can stand alone as being horrific occurrences whilst the pictures are as disconcerting as they are because of the fact that the things depicted therein really happened. The response against the pictures is not one calling for the stop of photography in prisons as much as it is a call for the stop of torture itself. The torture is what is inhumane, and it remains so even if no picture is taken of it occurring.

3) Images of war definitely should not be kept from public view during wartime because doing so deliberately misleads the population into believing things are much better than they really are. People have a right to know what is going on, not only because they are the ones going or being sent off to war, but also because they have the responsibility, if it is wrong, to change it.

So should the Abu Ghraib photos have been exhibited? Unequivocally, yes. These images brought to light for many people some of the atrocities that were occurring within US prisons. It forced the administration/military to own up a bit more, to do something about what was going on. As Sontag states, the pictures were “…necessary to get our leaders to acknowledge that they had a problem on their hands. After all, the conclusions of reports… about the atrocious punishments inflicted on 'detainees' and 'suspected terrorists'… have been circulating for more than a year… Up to then, there had been only words, which are easier to cover up… so much easier to forget.”

This idea that the human rights violations were simply ignored before the pictures came out is mirrored in the report by an independent panel headed by Schlesinger, “…the first to assign responsibility for the abuse of prisoners… to senior Pentagon officials including Defense Secretary Rumsfeld.” In the Abu Ghraib Timeline presented in “Inconvenient Evidence”, it says: “The report states that officials were aware of the problems at the detention facilities and failed to address them.”

The purpose of showing these images is thus to raise awareness of the occurrences and help to wake the people up to the truth of this war and its costs… not just to us, but also to the rest of the world. And it seems that the administration is aware of the power of these images to force change… which is precisely why they are afraid of them. Sontag in her article says that Rumsfeld acknowledged the existence of many more photographs and videos, and said: “If these are released to the public, obviously, it’s going to make matters worse.” Presumably, as Sontag states, it would be worse “for the administration…not for those who are the actual – and potential? – victims of torture.”

Not only can exhibiting these pictures help bring justice in the present, it can also provide the force to stop even more injustice in the future.

So while I don’t know about everyone else, I’m most assuredly willing to trade a bit of dissent for the safeguarding of justice and human rights.

Question 1

Most everything has an image or multiple images associated with it. War especially has images associated with it because it is such a huge thing in today’s world. The War on Terror or the War in

What does it mean to be an image of war? And just because an image may be of war, does that mean that it is “official”? An official image is one that has become “standard,” or incredibly recognizable. There are certain images that people think of when they think of the War on Terror. Several of these images are of the attacks on September 11, 2001, on the

Sometimes we can also see parallels between two wars, and images associated with those wars can show this. A famous photograph from World War II shows a flag being raised by soldiers amidst the clutter and rubble of battle in

During this war, the Iraqi government has been reformed into a crude democracy. Within the past few years, the first elections have occurred in

Question 2

“Sontag argues that we should ignore the images as such and focus on the events depicted in them.” I would absolutely agree with this argument. Yes, content in images can be dangerous; however, sometimes it is important for these images to be seen to get messages, themes, and news across. “Photographs have laid down the tracks of how important conflicts are judged and remembered.” In the modern world, photographs have become an integral part of history, and are extremely important. Take for example, the photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling over the body of a dead student at

Question 3

I am not a proponent of censorship of war photography; therefore I do not think it is right to hide war images during wartime. If a war is going on, people need to know about it. They best way to know about it is to see it. Photography has given our society that advantage. Whether or not such photographs are damaging does not matter. Being able to view these images, such as the photographs from Abu Ghraib, is such an asset to our society. It helps us see what war can do to our people, and to humankind. It is an atrocity, and yes these pictures paint a group of American soldiers and beastly and barbaric, but these photographs serve a purpose of anti-war. These images may prevent war from occurring again, or help resistance to war spread.

http://www.wgerlach.com/archives/disasters/index.html

http://www.britannica.com/eb/art/print?id=71966&articleTypeId=0

http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/thumbnail399.html

http://www.fairvote.org/blog/?p=20

http://www.talkingpointsmemo.com/images/2007-01-10_Mission_Accomplished.jpg

http://www.talkingpointsmemo.com/images/2007-01-10_Mission_Accomplished.jpg http://cache.boston.com/bonzai-fba/AFP_Photo/2006/09/28/1159438877_9412.jpg

http://cache.boston.com/bonzai-fba/AFP_Photo/2006/09/28/1159438877_9412.jpg

Soldiers can be seen bowing their heads in prayer in this image; thus, furthering the message that the Iraq War is a moral war that is being fought with honor and integrity and that God is on the side of the “good” guys.

http://blogs.trb.com/news/politics/blog/Bush%20Marines%20Iraq%20%20jim%20watson%20afp%20getty%20images-thumb.jpg

http://blogs.trb.com/news/politics/blog/Bush%20Marines%20Iraq%20%20jim%20watson%20afp%20getty%20images-thumb.jpg

George W. Bush can be seen speaking to a group of what appears to be hundreds of soldiers who appear to be listening intently and respectfully to everything the president is saying. By displaying this image, the government wants the American people to see that the troops who are giving their lives for their country support the president; therefore, those who are safe at home should also support the president. This image also shows that the commander-in-chief does care about those being sent off to war.

Part II

Images wield significant power and can thus be ideological and very harmful. Looking at the pictures in Inconvenient Evidence: Iraqi Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib disgusted and shocked me more than reading the accompanying text. Inscribed in these images is the potential to completely ruin the efforts the government is trying to make in Iraq; furthermore, with each new “unofficial” image emerging from the war, the reputation of the United States becomes even more tainted.

Sontag argues that the viewer should be more focused on the event occurring in the photo rather than the photo itself; however, the photo IS the evidence of the event. Without the images, the viewer would not be able to associate as much with the event than if an image was available. The image also serves to bond those who view it together: “Vernacular photography also serves a bonding purpose in its ability to create a sense of community and group identity among participants in events and between the participants in events and between the participants and the viewers” (Libby 45). Knowing this, if Sontag wants the viewer to focus on the event, then it would be more efficient to have the viewer focus on an image of an event. By concentrating on the images from Abu Ghraib, for example, the viewer can then center better on the events being depicted in the images.

Part III

Although they may be graphic and disturbing, images of war should not be kept from public view during wartime. It is the right of the people to know everything that is occurring as a result of the choices made by the leaders they elect into office. Photos that portray the cruel and dishonorable side of war, such as the Abu Ghraib photos, should definitely have been exhibited. Citizens must be made aware of the events occurring outside the borders of their respective countries. Many people harbor ideas of superiority in comparing their country to others. To say the least, many Americans instill in themselves the belief that they are untouchable when it comes to morality, honor, integrity, courage, and every other good virtue; however, because of the Abu Ghraib photos, we, along with others around the world, can see that this is not the case. These photos bring the harsh realities of the brutality and heartlessness of war into view better than any form of text ever could.

1. The term “official” brings to mind boy band fan clubs and facebook groups. Why would groups want to use such a term? Most likely, they use the term “official” to add a certain validity to the group; to show that the club or group represents the best interests of the subject. Some war images are considered “official” for similar reasons. Most often images are considered official when they are somehow endorsed by the subject. In the case of the war in Iraq, the military and, ultimately, the government are being portrayed, so they are generally the ones who, through the media, determine which images are deemed “official” and ok to represent the war. Several magazine covers depict such images. One “Times” magazine shows a woman wearing a combat hat and gazing off into the distance. If this does not spark patriotic vibes in a person, I don’t know what will. This image portrays not simply an American soldier, but a woman. By picturing a female, the magazine has accomplished two goals. First of all, as the caption reads, and her gender seems to imply, she is a mother. She has a family. Her role as not simply a soldier but a family member draws attention to all of the sacrifices members of the American military have been forced to make. Viewers tend to rally behind individuals they can relate to and sympathize with. Once the public supports the soldiers, they begin to support the war itself, or at least that’s what the government hopes will happen. The government, while not directly telling the media what to produce, is able to influence them by promoting certain images and stories. Another example of an “official” image appears on yet another “Times” magazine cover. The title boldly advertises “The Sinister World of Saddam,” and, by the look of the image, “sinister” is the perfect word to describe the image. The photograph portrays a tile mural in

2. “Practices of Looking” discusses the effect mass media can have on public opinion. As the article argues, the results of certain images can be incredibly powerful. We see an image of five happy people sitting around a dinner table and suddenly we know what a family is “supposed” to be. We see advertisements of women dressed in tiny clothes and wearing loads of makeup being followed by attentive male stalkers and we know what a woman is “supposed” to look like. The danger with such images is that they cause us to forget that we are “supposed” to be individuals, not clones of the images we see. The world is made up of many different people with many different beliefs and views. This diversity adds beauty to the world and makes it a better place to live by pulling on the strengths of a wide variety of people. Imagine how utterly meaningless life would seem if you walked out of your house one day to see that every woman had turned into Paris Hilton and every man had become Patrick Dempsey. Yet, so many people attempt to emulate the images they see that portray the “ideal” ways of life. Images tell us a lot of things about life that we are better off discovering ourselves. The visual has the ability to ignite emotions that the literal can barely touch. However, while images can have very powerful consequences, the real power is a result of the event or theme to which they refer. As the “Culture/War” article explains, image controversies “erupt along existing fault lines dividing highly polarized positions on social and political issues.” In other words, the “wars” that center around images are not “created” by the images themselves, but rather by some other issue already present in society. Sontag refers with frustration to peoples’ tendency to act “as if the fault or horror lay in the images, not in what they depict” (“Regarding the Torture of Others”). She is entirely right. Images are like telescopes. Their power is in allowing us to view certain phenomena, but they themselves are really quite unremarkable. In other words, images are powerful not because of what they are, but because of what they allow us to see.

3. “These pictures will not go away” (Sontag, “Regarding the Torture of Others”). These are perhaps the most powerful words in Sontag’s essay. Referring to the Abu Ghraib photos, Sontag is discussing the inability of the influence of the photos to be silenced. Once released, they had such an immediate, appalling, and memorable effect on the American public that there was no way to simply recall them and forget about them. They were already burned into the brains of millions of people across the globe. Some people argue that such images should be kept from the public, especially in times of war. They argue that the images will only create anger. They are entirely right: the images will create anger. In a war against terrorism, “some of our own” are terrorizing “the enemy.” This event SHOULD create anger. People SHOULD get mad. By exhibiting the photos in the International Center of Photography, people got angry; they grew passionate, as they should have. Nearly every great change in American history is the result of people with passion. When there are injustices in the world, people have a duty to stand up for humankind. If that means people have to see images that they are not “comfortable” with, then so be it.