P.S. David would like it to be know that he, David Vanderford Celis, came up with the idea for the blog. No one wants to incur his wrath.

Blog space for critical reflections on course material for Culture Wars: Politics, Ethics, + Aesthetics

Well it looks like this class is over. But why let this blog go to waste? I’ve always wanted somewhere to write about my daily activities so I think I will take the opportunity to share them with the other members of my class.

Today I had a physics review, so I had to get up kind of early. 9:30, which was early compared to when David woke up. He said the only thing he remembered from this morning was me opening and shutting the door about twenty times. That’s why when I sleep, I use earplugs.

Some drunk people were hollering over their game of Madden NFL this morning, which made me want to go home even more. I kind of miss my dog too.

Shea went home today and David and I were a bit upset to see her go. We’ll be pretty bored as we play Dawn of War and World of Warcraft until Friday.

I think tension is starting to mount between me and David. Today he made a post on his blog about how loud my rave music is. I wear headphones so he doesn’t have to hear it! Ughhh maybe I should tell him how annoying it is to hear him studying late at night when I try to go to bed at 11 pm. Those page turns don’t need to be that loud. I don’t know how I’m going to live through another semester like this!

1.) War images become “official” through repetition and their power to symbolize ideologies. The image achieves this “official” status from government and media support. It is backed by the government’s effort to keep it in circulation, and the media prints it in magazines and newspapers, plasters it on billboards, and floods the televisions. War becomes a single moment, whether in a real photograph or a cartoon-drawn image, and ideas are represented within this moment. The reason these ideas are supported by the government and by the people (either of their own accord or as a result of the government-supported media portrayal) is that they confirm specific identities of the nation that are desirable in a time of war. These identities are based on patriotism and concepts the nation considers itself to hold valuable, such as human rights and environmental welfare. The “official” image depicts exactly what mass society wants to believe about its government and the role it plays in the war. It embodies the very reasons we justify our fighting, as well as the reasons we believe our cause is worth soldiers’ lives. We want to believe that our part in the war is for the better of the world, and so the “official” image strokes our ego and confirms this for us. Inevitably the image possesses a political agenda, but it is one we want to uphold as a nation. “Official” war images serve exactly the purpose Plato describes in The Republic, one of empowering the nation toward unification and progress.

The following images satisfy their position of being “official” through similar portrayals of American ideology. The first displays an American soldier helping a small Iraqi child. Not only does this show the generosity and compassion of Americans in bringing medicine to those less fortunate, but the happy mother in the background shows us approval and gratitude for our actions from the Iraqis. The second image shows Muslims and Christians working together to reopen St. Jude’s. This image becomes a sign that

2.) In “Regarding the Torture of Others” Susan Sontag may present the argument that images should be ignored as ideological and that we should focus rather on the events depicted by the photo. But this she addresses as a factor in the corruption of American leadership. Sontag herself does not deny the capacity of photographs to hold ideological values. She recognizes that they are causing an issue not just because of “what the photographs reveal to have happened,” but also as a result of more implicit meanings the images possess. Sontag addresses that a further problem is that the pictures were used as “trophies” and the “perpetrators apparently had no sense that there was anything wrong in what the pictures show.” She hardly wants us to ignore the images as separate from ideologies when she makes the claim that they illustrate the “culture of shamelessness (and) the reigning admiration for unapologetic brutality” that has increasingly become accepted as entertainment in

An analysis of the pictures and not necessarily of their depictions, however, reveals even further portrayals of ideologies. As Susan Libby explains in her “Culture/War” article, elements of the picture itself such as camera angle, character of being an “everyday picture,” gaze of the people present, and even the fact that someone controlled the camera as the picture was taken all play a part in a picture’s ideological implications. These specific aspects when applied to the Abu Ghraib photographs reveal principles of domination, control, and inequality (Libby). They become dangerous as they are circulated to the public, and these ideologies are presented to society through the visual representations.

What is depicted in the Abu Ghraib photos directly reflects many of the same ideologies that can be found in the analysis of the pictures as vernacular photography. This can actually lessen the degree of harmful potential because those who do not accept the explicit are likely to not accept the implicit either. Thus in this case viewers of the public can reject the violence they see being depicted simultaneously with the latent ideas of domination and control. As Libby points out, visual representation is about “controlling our knowledge,” something that is utilized heavily in the political world. The real dangers arise when ideologies are imbedded within a picture that people accept. The best example of this concept is a picture that actually depicts something agreeable with the viewer, but is imbedded as an image with ideological ideas possessing harmful values. An image previously discussed in this course, Roses for Stalin by Vladimirski shows an agreeable photo of children giving roses to Joseph Stalin. Some underlying messages here that can be delivered furtively through the positive exterior are of communism, dictatorship, and male domination. This idea of the public more readily identifying accepting the explicit part of the image and consequently accepting the implicit is discussed in “Mass Media and the Public Sphere” as the “hypodermic effect” effect of mass media. This refers to “an increased passivity in viewers ‘drugged’ by media texts with less explicitly political messages.” When performed, it can become a “means of domination” on the masses of people by “‘selling’ them ideas through the media” (Sturken). Photos can have the same effect even if they have parallel meanings, but that are used to represent something that is not congruent with the two. Take the example of when only pictures that project a positive image of our efforts in a war are shown. The actual depiction may be something positive just as the ideologies represent (see photos from question #1), but they do not offer the full scope of the situation. The negative aspects are not represented. As to what is harmful ideology is to a degree up to discretion, but when the minds of the masses can be controlled by hidden or completely absent ideologies, there is great danger in the corruption of societies.

The separation of the photos from ideologies does make for successful politics, though. Those in the Bush Administration can then claim to be shocked and appalled at the photos, since they do not represent the “‘true nature and heart of America’” (Sontag). This separation, though, is like putting on a neck brace—they can cover up the problem and prevent further damage, but they are not actually going in and reconstructing and fixing the framework. And yet do we blame them so readily without any ideas of alternative methods? Analyzing ideologies and working to change them requires the removal of longstanding accepted ideas. Not only does it require the deconstruction of present ideologies, but new ones must be ready to successfully establish in their absence. This takes a great amount of time and effort, and the people of a country need immediate attention as well as perseverance through time. And we cannot forget that new ideologies can most certainly not be accepted or instilled by authorities who the masses do not trust.

2.) With all of this in mind it is important not only for those in control of the dissemination of images to be conscious of the vulnerable public they are providing for, but it is important for us as viewers to be critical of the information we are presented. Censorship has many fine lines, and there should be differences between what can be shown in an elementary school classroom and what an adult citizen can view by choice. Images of war may be kept from the view of younger audiences, but should not be kept from the public at large, especially the public of the country actually in the war. The exhibition of photographs is just as important during war as during a time of peace. Just because something is already in progress does not constitute the need for its continuation, and photos that question the movement of the war thus become very important in its path. The Abu Ghraib photos provide a perfect demonstration of the horrors of war that we are often sheltered from. Without exhibition, actions may not be accounted for, and the terrible things people are capable of can be allowed to proceed. By excusing accountability we often excuse responsibility, and not only can actions continue, but the dangers can escalate if those performing them have no one watching and thereby no one holding them accountable. Alas it is evident that even the exposition of these horrors does not always lead to their demise, but we cannot expect anything to change if the images remain hidden from the public eye.

1. War images can become official through government or media proclamation. In either case, such images must be easily recognizable and also emotionally charged in order to come into widespread use. These images are usually propagated by the media, which will reuse them again and again in order to avoid the need to find new material of the same quality, and because of viewer identification with the images due to familiarity. If the images reinforce a particular view of a war, then this view must be held by a large majority of the people in order to become well known.

The first image, perhaps the most widely known so far of the Iraq War, is of the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue after the invasion. There are actually hundreds of images of this – because it was staged as a media event by the military. Civilians were brought in from a village to produce a fake crowd, and they watched as the statue was pulled down. In most photographs, it appears as if a large crowd was present but this was due to the framing of the picture. In this particular shot, the large empty areas can be seen, making it evident that support for

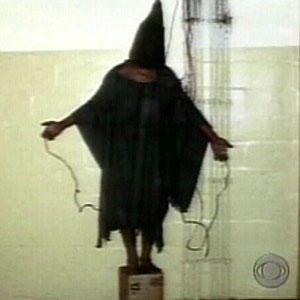

The photograph of a detainee in a black shroud and hood standing on the box is the most often reproduced image of the Abu Ghraib photographs, which number over eighteen hundred. This image is most often used because it is not offensive, and the media tries to self censor itself in order to keep viewers. The more sexual Abu Ghraib photographs are typically not shown. Also the anonymous man (who has since been identified, but he is still masked) stands on a box that resembles a pedestal, while spreading his arms in the typical pose of the martyr – the cross. But instead of having his hands nailed, they are attached to electrodes, a more modern version of a painful death. These images were originally taken to serve the interest of the soldiers who conducted interrogations, but now they have been used by anti-war activists as the icon of protest.

A picture from a gallery on the official White House website entitled “Photos of Freedom” shows marines distributing food to civilians. The behavior in the photograph is civil – there are no riots breaking out over limited rations. The truck is also fully loaded with supplies – showing

2. While I believe that the need for reform emphasized by images such as the Abu Ghraib photographs are a primary concern, I think that downplaying the images as Sontag suggests will lead to a lesser understanding of the events themselves. We must understand what we decide to condemn, and only by deep examination of the images can this be done. The most important thing to ask about any image is “why was this created?” The answer to this will reveal the bias. All photographs are biased, since they only offer an edited version of reality. Only what lies between the borders of the lens, and happened in the fraction of a second of exposure is often promoted as a true and unbiased account, although it will be laced with ideology.

The irony here is that the Abu Ghraib photographs were taken by soldiers promoting the abuse, but now they are used to condemn it. The conflict in ideology seems almost sick – the soldiers smiling behind the naked bodies of detainees forced into humiliating poses. While with one photograph there is some doubt about the events that occurred around it, and the image’s staging, there is much less doubt with a series. There were over eighteen hundred photographs of the Abu Ghraib incidents, which showed the evolution of different torture sessions so that some sense of the passage of time could be gained through still images.

While these considerations seem to remove most of the uncertainty around the events, they also continue to propagate the misconception that photographs are a perfect form of truth. Just because some photographs tell the same story that occurred does not mean that others will be so candid. These misconceptions are harmful to visual literacy and the examination of ideology behind images – the lack of such scrutiny leaves one vulnerable to propaganda.

3. In a democratic society, the voters must be informed politically in order to make the most informed decisions. Withholding any sort of information necessarily compromises this, yet there are instances of national security where the public must be kept in the dark. But the effect of a war is not one of these areas. The public needs to know what exactly they are voting for directly, or what their elected representatives are voting for. If the war has gone into stalemate, the “enemy” is being tortured for dubious reasons, and civilians are dying, then people must know so the war can be reconsidered with these factors in mind.

There is a difference between images of offensive and defensive conflicts. The offensive conflict is inherently an ethical issue, since a decision must be made to engage in violence or not. A defensive conflict presents no option – rise and fight, or be annihilated. If there is no justifiable reason to be engaged in offensive conflict, then the citizens of a nation have a right to make the decision to end it. Also, war should not be used as a common tool to force the compliance of smaller, less stable nations. War devastates everything, and supporters need to know the consequences of authorizing violent force. There should be no censorship whatsoever in this case.

In a defensive war, the nation’s very existence may be at stake. But if there is no threat of annihilation, then involvement should be minimal and not include “revenge” actions, such as the Iraq War today. Thus again, there should be no censorship of war images, so that the public does not seek out revenge, because of the pain it will inflict on the innocent. This only leads to the escalation of conflict anyway – as we further fight terrorists, we cause more of them to rise up against us than there were to begin with.

When the nation is indeed about to be toppled, as the Soviet Union nearly was in 1941 by Nazi Germany, then the government must do all it can to resist destruction. The injustices inflicted by the government on its own people will be nothing compared to the enemy’s wrath. Certainly censorship of war images to keep morale high would be acceptable as an alternative to rape and slaughter of the citizens, at the hands of some other force. But another alternative would be to use images of violence directed against the “good guys” in order to motivate the nation to stand strong and resist, because the images will remind them of their fate if the nation’s struggle fails.

The Abu Ghraib photographs should not have been withheld from the public. When they were eventually leaked, the negative reaction against the Army was much greater than it would have been if the offending soldiers and been summarily punished. The cover up was a form of tacit approval of the tactics carried out at Abu Ghraib. While I think that the public has a right to know about offensive wars it is engaged in, I do not think the photographs should have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography. Association with an artistic institution almost praises the photographs in a way, because they acknowledge something about the nature of war. But these photographs never should have existed in the first place, so they should not be associated with art. Also, these photographs were taken as trophies by the soldiers, in order to glorify their dominance over the prisoners and also to humiliate them. The victims’ rights should be taken into account, as they were forced to participate in the photographs, and then had them used in blackmail during interrogations. The fear of being seen in such impious poses (the homosexual poses in the context of Islam) by others made prisoners comply, but now thousands of people will see them, adding to the humiliation. The public has a right to know the war though images in the media, and the media will self-censor itself to a large degree, which would filter out the most degrading of the photographs. But putting them up on display is furthering the emotional damage done to the detainees.

Image Sources (From left to right):

http://www.dannyrudd.com/brokenmedia/images/statue.jpg

http://peacework.blogspot.com/uploaded_images/Abu%20Ghraib%20Torture-715244.jpg

http://www.whitehouse.gov/infocus/iraq/photoessay/essay1/09.html