1. War images can become official through government or media proclamation. In either case, such images must be easily recognizable and also emotionally charged in order to come into widespread use. These images are usually propagated by the media, which will reuse them again and again in order to avoid the need to find new material of the same quality, and because of viewer identification with the images due to familiarity. If the images reinforce a particular view of a war, then this view must be held by a large majority of the people in order to become well known.

The first image, perhaps the most widely known so far of the Iraq War, is of the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue after the invasion. There are actually hundreds of images of this – because it was staged as a media event by the military. Civilians were brought in from a village to produce a fake crowd, and they watched as the statue was pulled down. In most photographs, it appears as if a large crowd was present but this was due to the framing of the picture. In this particular shot, the large empty areas can be seen, making it evident that support for

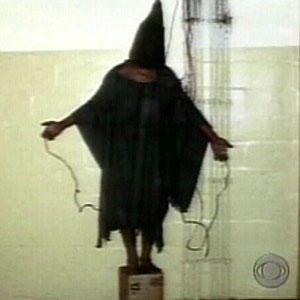

The photograph of a detainee in a black shroud and hood standing on the box is the most often reproduced image of the Abu Ghraib photographs, which number over eighteen hundred. This image is most often used because it is not offensive, and the media tries to self censor itself in order to keep viewers. The more sexual Abu Ghraib photographs are typically not shown. Also the anonymous man (who has since been identified, but he is still masked) stands on a box that resembles a pedestal, while spreading his arms in the typical pose of the martyr – the cross. But instead of having his hands nailed, they are attached to electrodes, a more modern version of a painful death. These images were originally taken to serve the interest of the soldiers who conducted interrogations, but now they have been used by anti-war activists as the icon of protest.

A picture from a gallery on the official White House website entitled “Photos of Freedom” shows marines distributing food to civilians. The behavior in the photograph is civil – there are no riots breaking out over limited rations. The truck is also fully loaded with supplies – showing

2. While I believe that the need for reform emphasized by images such as the Abu Ghraib photographs are a primary concern, I think that downplaying the images as Sontag suggests will lead to a lesser understanding of the events themselves. We must understand what we decide to condemn, and only by deep examination of the images can this be done. The most important thing to ask about any image is “why was this created?” The answer to this will reveal the bias. All photographs are biased, since they only offer an edited version of reality. Only what lies between the borders of the lens, and happened in the fraction of a second of exposure is often promoted as a true and unbiased account, although it will be laced with ideology.

The irony here is that the Abu Ghraib photographs were taken by soldiers promoting the abuse, but now they are used to condemn it. The conflict in ideology seems almost sick – the soldiers smiling behind the naked bodies of detainees forced into humiliating poses. While with one photograph there is some doubt about the events that occurred around it, and the image’s staging, there is much less doubt with a series. There were over eighteen hundred photographs of the Abu Ghraib incidents, which showed the evolution of different torture sessions so that some sense of the passage of time could be gained through still images.

While these considerations seem to remove most of the uncertainty around the events, they also continue to propagate the misconception that photographs are a perfect form of truth. Just because some photographs tell the same story that occurred does not mean that others will be so candid. These misconceptions are harmful to visual literacy and the examination of ideology behind images – the lack of such scrutiny leaves one vulnerable to propaganda.

3. In a democratic society, the voters must be informed politically in order to make the most informed decisions. Withholding any sort of information necessarily compromises this, yet there are instances of national security where the public must be kept in the dark. But the effect of a war is not one of these areas. The public needs to know what exactly they are voting for directly, or what their elected representatives are voting for. If the war has gone into stalemate, the “enemy” is being tortured for dubious reasons, and civilians are dying, then people must know so the war can be reconsidered with these factors in mind.

There is a difference between images of offensive and defensive conflicts. The offensive conflict is inherently an ethical issue, since a decision must be made to engage in violence or not. A defensive conflict presents no option – rise and fight, or be annihilated. If there is no justifiable reason to be engaged in offensive conflict, then the citizens of a nation have a right to make the decision to end it. Also, war should not be used as a common tool to force the compliance of smaller, less stable nations. War devastates everything, and supporters need to know the consequences of authorizing violent force. There should be no censorship whatsoever in this case.

In a defensive war, the nation’s very existence may be at stake. But if there is no threat of annihilation, then involvement should be minimal and not include “revenge” actions, such as the Iraq War today. Thus again, there should be no censorship of war images, so that the public does not seek out revenge, because of the pain it will inflict on the innocent. This only leads to the escalation of conflict anyway – as we further fight terrorists, we cause more of them to rise up against us than there were to begin with.

When the nation is indeed about to be toppled, as the Soviet Union nearly was in 1941 by Nazi Germany, then the government must do all it can to resist destruction. The injustices inflicted by the government on its own people will be nothing compared to the enemy’s wrath. Certainly censorship of war images to keep morale high would be acceptable as an alternative to rape and slaughter of the citizens, at the hands of some other force. But another alternative would be to use images of violence directed against the “good guys” in order to motivate the nation to stand strong and resist, because the images will remind them of their fate if the nation’s struggle fails.

The Abu Ghraib photographs should not have been withheld from the public. When they were eventually leaked, the negative reaction against the Army was much greater than it would have been if the offending soldiers and been summarily punished. The cover up was a form of tacit approval of the tactics carried out at Abu Ghraib. While I think that the public has a right to know about offensive wars it is engaged in, I do not think the photographs should have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography. Association with an artistic institution almost praises the photographs in a way, because they acknowledge something about the nature of war. But these photographs never should have existed in the first place, so they should not be associated with art. Also, these photographs were taken as trophies by the soldiers, in order to glorify their dominance over the prisoners and also to humiliate them. The victims’ rights should be taken into account, as they were forced to participate in the photographs, and then had them used in blackmail during interrogations. The fear of being seen in such impious poses (the homosexual poses in the context of Islam) by others made prisoners comply, but now thousands of people will see them, adding to the humiliation. The public has a right to know the war though images in the media, and the media will self-censor itself to a large degree, which would filter out the most degrading of the photographs. But putting them up on display is furthering the emotional damage done to the detainees.

Image Sources (From left to right):

http://www.dannyrudd.com/brokenmedia/images/statue.jpg

http://peacework.blogspot.com/uploaded_images/Abu%20Ghraib%20Torture-715244.jpg

http://www.whitehouse.gov/infocus/iraq/photoessay/essay1/09.html